Despite signing a $1 billion agreement with the First Nations Leadership Council that includes advancing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), Canadian governments continue to greenlight logging, mining, fish farming, and other impactful activities inside IPCAs, the Tyee reports.

Contracts and licenses for these resource extraction projects are often granted against the wishes of Indigenous nations. As a result, Indigenous governments have had to resort to buying out tenures from these companies as a way of enforcing their IPCA rules.

There is a mechanism to pause resource extraction activities, known as “cooling-off periods.” These periods are meant for Indigenous nations to plan and negotiate with industry on the rules of the IPCA.

However, during this process, Indigenous governments often find themselves without adequate legal protection. Many IPCAs are not designated under Canadian protected area legislation. This means that the affected Indigenous governments are not able to effectively seek additional legal protection for their IPCAs as they are only covered by regular protected area designations that limit Indigenous authority.

The troubles don’t end there.

Despite the $1 billion agreement, there aren’t enough funds to go around for all the IPCAs that need them. Only a small percentage of projects actually get funding. The Tyee speculates that this could sometimes be due to disagreements between Indigenous governments and industry over the allowance of resource extraction in IPCAs.

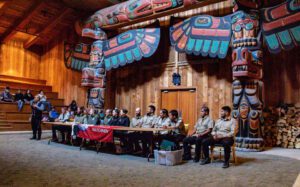

IPCAs have a powerful potential to transform outcomes for BC’s over-exploited resources. In 2021, the Gwaxdlala/Nalaxdlala (Lull Bay/Hoeya Sound) area of Knight Inlet – representing 10,416 hectares of BC’s central coast – was declared an IPCA by the Mamalilikulla First Nation.

Under their stewardship, the Mamalilikulla have been able to raise their pink salmon fish stock dramatically. The Mamalilikulla counted just 26 pink salmon in three watershed areas in 1920. In just one year following the IPCA announcement, they counted 500 pink salmon in the mouth of a single watershed.

Despite their results, even the Mamalilikulla are concerned about the lack of funding and resources for their Indigenous stewards as well as a lack of enforcement authority.

The onus to alleviate these challenges lies with Canadian governments, who must honour their agreements with the Indigenous peoples of BC’s coast – not just to facilitate effective Reconciliation efforts, but also to ensure BC’s natural resources thrive and have the ability to enrich the economy that so heavily depends on them in the long run.

Read this Tyee article for a more in-depth look into the challenges Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas face and check out this West Coast Now article to learn more about the Mamalilikulla IPCA.