While Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) reports compliance with bycatch limits in Pacific groundfish trawl fisheries, growing scientific evidence suggests that actual mortality rates for many non-target species far exceed what is officially acknowledged.

In British Columbia’s trawl fisheries, non-target species such as halibut, salmon, sharks, skates, crabs, and deep-sea invertebrates are routinely caught and discarded. Though industry practices frame these releases as “non-lethal,” the biological reality is stark: many of these discarded marine animals do not survive. For some species, survival is functionally zero, a fact supported by research but underrepresented in public reporting.

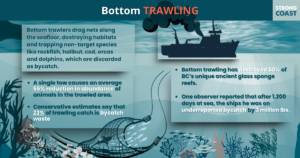

On average, trawlers discard 23% of their catch as bycatch, though this number is likely underestimated. This includes not only non-target species, but also juvenile fish and undersized individuals of the target species. These fish are often thrown back, dead or dying, negatively impacting future generations.

Halibut Mortality Often Goes Unrecognized

Pacific halibut, while more hardy than some species, suffer high mortality when captured in trawl nets. Trawl-caught halibut are not permitted for retention and must be discarded, but survival rates depend heavily on handling and release conditions.

DFO management guidelines apply different mortality rates based on observed fish condition, ranging from 20% for halibut released in “excellent” shape to 90% for moribund individuals. However, these estimates are derived from controlled studies and do not reflect the delays, deck exposure, and injuries that occur during actual fishing operations. More recent tagging research has confirmed that delayed release, long tow times, and rough handling significantly increase mortality. In practice, mortality for discarded halibut in trawl fisheries frequently ranges from 50% to over 90%.

Most Salmon Do Not Survive Trawl Capture

Pacific salmon, primarily Chinook, are a prohibited species in groundfish trawls. Nevertheless, they are caught in significant numbers. In the 2022/23 fishing year, over 28,000 salmon were caught as bycatch, with Chinook representing 93% of the total, a species vital to Indigenous communities and a primary food source for endangered Southern Resident killer whales. Notably, the bycatch numbers for salmon remained essentially unchanged in the 2023/24 season.

Survival of trawl-caught salmon is assumed to be negligible. No formal post-release mortality studies exist in Canada, but DFO acknowledges that trawl conditions are highly lethal. Salmon are not built to withstand net capture, crowding, and extended air exposure. Most die shortly after entrapment, and many are already dead when pulled aboard. Discarding these fish does not equate to release; it equates to loss.

Elasmobranch Survival Depends on Conditions

Skates and dogfish, two common elasmobranch bycatch species, show variable mortality based on species, gear type, and handling. In Canadian trawl fisheries, skates are estimated to experience 50% mortality. Their flattened bodies and physical resilience allow some to survive short air exposure, but longer tow and deck times reduce their survival prospects.

Dogfish (Squalus acanthias), which lack swim bladders and tolerate low oxygen, often survive initial capture. Some studies suggest discard mortality for dogfish may be under 50%, especially in light tows. However, delayed mortality due to stress or injury may still occur, and most Canadian assessments apply a 50% mortality estimate as a conservative management tool.

Invertebrate Deaths Are Largely Uncounted

Crabs, echinoderms, and seafloor-dwelling invertebrates suffer extensive mortality from bottom trawling, yet are largely excluded from formal bycatch reporting. In soft-bottom areas, trawl nets regularly capture Dungeness and Tanner crabs, many of which are juveniles. Studies estimate 40–60% mortality in trawl-caught crabs due to crushing, limb loss, and exoskeletal damage.

Echinoderms such as sea stars, brittle stars, and sea urchins experience high death rates from gear contact. A single trawl pass has been shown to reduce sea star abundance by 10–30%. Collie et al. estimate that a single trawl tow results in a 55% reduction in the overall abundance of animals in the affected seafloor area, which clearly puts the affected ecosystem at risk.

Bottom trawling also has severe impacts on cold-water coral and sponge habitats. Once dislodged, these immobile organisms almost always die. Historical trawling in BC damaged an estimated 50% of known glass sponge reef habitat before protections were enacted. Mollusks and soft-bodied sea floor animals are similarly vulnerable, with 20–50% mortality reported in trawl paths.

A Monitoring System in Decline

Until 2020, DFO relied on at-sea observers aboard trawl vessels to document bycatch, species composition, and compliance with fishing regulations. These observers played a key role in ensuring transparency, but the system has long faced scrutiny. Reports from inside the observer program detail a culture of harassment, intimidation, and bribery, with observers pressured to underreport infractions or look the other way.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, the onboard observer program was suspended, but trawling operations continued. Human observers were hastily replaced with electronic monitoring systems, favoured by the industry. Yet these systems lack the ability to fully assess conditions, injury, and behaviour in real-time.

During the 2022/23 fishing season, enforcement patrols documented multiple violations by trawl vessels, including missing or malfunctioning cameras, dirty lenses, inadequate camera coverage, and missing fish slips. Since much of the trawling occurs offshore, beyond regular surveillance, the true extent of violations is almost certainly higher than reported.

The Mortality Gap Has Lasting Consequences

The gap between reported and actual mortality in Pacific trawl fisheries has significant ecological consequences. While logbooks and quotas may present a picture of managed, sustainable harvests, mortality from bycatch is far greater than what is documented.

The biological reality is that many discarded bycatch species, from salmon and halibut to invertebrates, are dead or dying by the time they leave the vessel. Current estimates often fail to account for delayed mortality, post-capture trauma, and unmonitored species groups. In some cases, mortality assumptions have not been updated despite newer data showing that survival depends heavily on specific tow conditions, gear use, and handling.

Global biodiversity is already under immense pressure. Limiting industrial-scale, non-selective extraction methods like trawling is one of the most impactful steps that can be taken to protect species at risk and preserve marine ecosystems.

Accurate bycatch mortality estimates are essential for informed decision-making and effective conservation. Without them, fisheries management risks ignoring the full scope of its ecological footprint and jeopardizing the long-term sustainability of Canada’s Pacific waters, ultimately putigm the livlihoods of msy coastal residents and communities at risk.

Stopping Bycatch at Its Source

Marine protected areas (MPAs) that fully prohibit trawling can provide vital marine habitat relief from bycatch. By banning the use of non-selective nets in sensitive habitats, MPAs remove the primary source of incidental capture for species like Chinook salmon, halibut, skates, corals, and sponges. This not only stops the immediate mortality caused by trawl gear but also prevents the long-term habitat destruction that leaves marine ecosystems less able to support diverse species.

Over time, these trawl-free zones can counteract the ecological losses caused by decades of bycatch through what’s known as the “seeding effect.” As fish and invertebrate populations inside an MPA grow older, larger, and more productive, they produce more offspring. Larvae and juvenile fish drift or swim beyond the MPA’s borders, boosting populations in surrounding areas where fishing is allowed. This natural replenishment helps rebuild stocks that have been diminished by years of incidental catch. This “seeding effect” (also known as spillover) has enhanced fish stocks and sustainable catch globally.

For small-scale and Indigenous fishers in British Columbia, this spillover can bring tangible benefits: sustainable fisheries, increased catch closer to home, reduced travel costs, and healthier nearshore ecosystems that support a wide variety of culturally and economically important species. In this way, MPAs not only stop the damage from trawling-driven bycatch, but also reverse the damage done, supporting both biodiversity and the coastal communities that depend on it.